better that I be defeated, even killed, than to learn the ways of

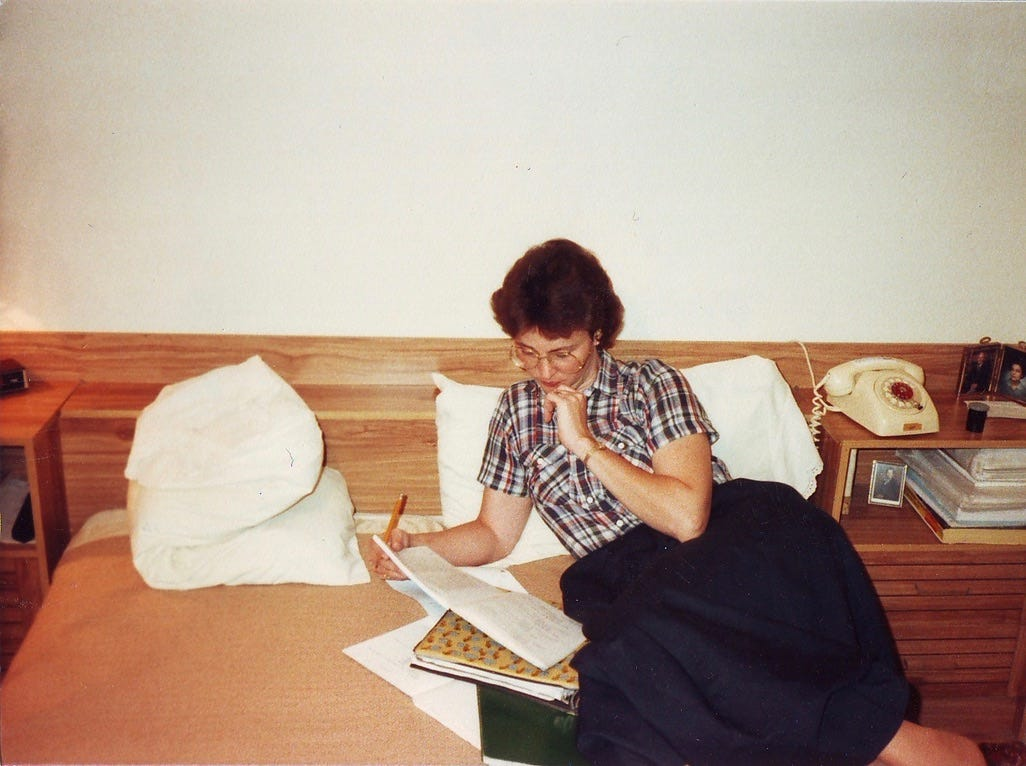

Gleanings from Great Books

“Rebels who ascend to the throne by rebellion have no patience with other rebels and their rebellions. When Absalom is faced with rebellion, he will become a tyrant. He will bring ten times the evil he sees in your present king. He will squelch rebellion and rule with an iron hand . . . and by fear. He will eliminate all opposition. This is always the final stage of high-sounding rebellions. Such will be Absalom’s way if he takes the throne from David.”

“It is better that I be defeated, even killed, than to learn the ways of . . . of a Saul or the ways of an Absalom. The kingdom is not that valuable. Let him have it, if that be the Lord’s will. I repeat: I shall not learn the ways of either Saul or Absalom.

Gene Edwards, The Gene Edwards Signature Collection: A Tale of Three Kings / the Prisoner in the Third Cell / the Divine Romance (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale Momentum, 2016).

Taylor, however, was never happy living among the other missionaries. In his eyes they lived in luxury. There was no place in the world, he said, where missionaries were more favored than in Shanghai. He viewed most of them as lazy and self-indulgent, and beyond that, he characterized the American missionaries as “very dirty and vulgar.” He was only too anxious to get away from their “criticizing, backbiting and sarcastic remarks,” so less than a year after he arrived in China he began making journeys into the interior. On one of these trips he traveled up the Yangtze River and stopped at nearly sixty settlements never before visited by a Protestant missionary.

Ruth A. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya: A Biographical History of Christian Missions, Second Edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004), 188.

The voyage to China was a remarkable one. Never before had such a large mission party set sail with the mission’s founder and director on board, and the impact on the ship’s crew was noticeable. By the time they had rounded the Cape, card playing and cursing had given way to Bible reading and hymn singing. But there were problems as well. The “germs of ill feeling and division” had crept in among them, and the once-harmonious band was sounding dissonant chords before it reached its destination. Lewis Nicol, a blacksmith by trade, was the ringleader of the dissenters. He and two other missionaries began comparing notes and came to the conclusion that they had received less substantial outfits than were usually received by Presbyterians and other missionaries. With that complaint came others: “The feeling among us appears to have been worse than I could have formed any conception of,” wrote Taylor. “One was jealous because another had too many new dresses, another because someone else had more attention. Some were wounded because of unkind controversial discussions, and so on.”33 By talking to each missionary “privately and affectionately” Taylor was able to calm the dissention, but underlying feelings of hostility remained that would soon culminate in a near collapse of the infant CIM.

Ruth A. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya: A Biographical History of Christian Missions, Second Edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004), 193.

In the aftermath of the Yangchow controversy, as critical newspaper editorials and private letters reached China, Taylor became deeply depressed—so much so that he lost his will to go on, even being tempted to end his own life. He was confronting the most serious spiritual battle of his life: “I hated myself; I hated my sin; and yet I gained no strength against it.” The more he sought to attain spirituality, the less satisfaction he found: “Every day, almost every hour, the consciousness of failure and sin oppressed me.” He was at the point of a mental collapse when he was, by his own account, rescued by a friend. Aware of Taylor’s problem, the friend, in a letter, shared his own secret to spiritual living: “To let my loving Savior work in me His will.… Abiding, not striving or struggling.… Not a striving to have faith, or to increase our faith but a looking at the faithful one seems all we need.” With that letter Taylor’s life was changed: “God has made me a new man.”

Ruth A. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya: A Biographical History of Christian Missions, Second Edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004), 194–195.

Years earlier, when Emily and Jennie were living at the mission house in Hangchow with the Taylors, Lewis Nicol had spread rumors that Taylor was giving the young women good-night kisses and more. In his effort to discredit Taylor, he carried his charges to George Moule, an Anglican missionary who strongly opposed the ministry of single women. Moule called for an informal trial and questioned both Taylor and the young women. There was no evidence of wrongdoing—except bad judgment. The living arrangement that appeared inappropriate to some Western missionaries looked no different than polygamy to the Chinese.

Ruth A. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya: A Biographical History of Christian Missions, Second Edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004), 196.

This is where you live as a Christian. We live between the great reality that in Christ there’s no condemnation, and in him we never know any separation from the love of God.

We’ve fallen away from the truth of our original blessedness. The knowledge of God as Father has been lost through sin, corruption, and rebellion (Rom 1:18–32) with the result that we’ve turned in on ourselves, seeking to meet our own desires at the expense of others. We’re at war first with ourselves and with our unmet desires, and then we’re at war with each other as we seek to use each other to meet those desires. No wonder we’re trapped in a cycle of complaining, grumbling, fighting, and forcing! Strife on a global scale has its origin in the loss of the knowledge of God our Father.

Yet the truth of the matter is that only in the recovery of that knowledge, only in a wholly dependent relationship with God the Father through his Son, are we whole and our desires met.

A harsh view of others deflects away from ourselves the shame and guilt we feel in our own hearts.

If we don’t see and believe ourselves to be loved completely by God through Jesus, then distrust will create a chasm in our relationship with God, which the flesh, the world, and the devil will fill with fear. And when our hearts are filled with fear, our relationship with the Father becomes something we toil at in self-justification rather than receive as a gift of grace.

Retain a single shred or fragment of legality with the gospel, and we raise a topic of distrust between man and God. We take away from the power of the gospel to melt and to conciliate. For this purpose, the freer it is, the better it is.

Daniel Bush and Noel S. Due, Embracing God as Father: Christian Identity in the Family of God (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014).

•Derogatory assumptions

•Sharp, cutting comments

•A grudge that feels increasingly heavy inside you

•The desire for the one that hurt you to suffer

•Anxiety around the unfairness of other people’s happiness

•Skepticism that most people can’t be trusted

•Cynicism about the world in general

•Negativity cloaked as you having a more realistic view than others

Bitterness wears the disguises of other chaotic emotions that are harder to attribute to the original source of hurt.

•Resentment toward others whom you perceive moved on too quickly

•Frustrations with God for not doling out severe enough consequences

•Seething anger over the unfairness of it all that grows more intense over time

•Obsessing over what happened by replaying the surrounding events over and over

•Making passive-aggressive statements to prove a point

•One-upping other people’s sorrow or heartbreak to show your pain is worse

•Feeling justified in behaviors you know aren’t healthy because of how wronged you’ve been

•Snapping and exploding on other people whose offenses don’t warrant that kind of reaction

•Becoming unexplainably withdrawn in situations you used to enjoy

•Disconnecting from innocent people because of the fear of being hurt again

•Irrational assumptions of worst-case scenarios

•Demanding unrealistic expectations

•Refusing to tell the person who hurt you what’s really bothering you

•Stiff-arming people who don’t think the same way you do

•Rejecting opportunities to come together and talk about things

•Refusing to consider other perspectives

•Blaming and shaming the other person inside your mind over and over

•Covertly recruiting others to your side under the guise of processing or venting

Lysa TerKeurst, Forgiving What You Can’t Forget: Discover How to Move On, Make Peace with Painful Memories, and Create a Life That's Beautiful Again (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2020), 175–176.

Bitterness doesn’t have a core of hate but rather a core of hurt.

Lysa TerKeurst, Forgiving What You Can’t Forget: Discover How to Move On, Make Peace with Painful Memories, and Create a Life That's Beautiful Again (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2020), 177.